Yes, it’s been a whirlwind 2 weeks!

First things first – I hope that you and your family are safe, happy and healthy. I have many thoughts concerning the various trials that we are currently facing – but for now I’ll keep things light and let you know about the fun time I’ve had with protocols, address translation, address prefixes, Apache configs… ya, it’s been fun.

So this all started out with a desire to up my Internet bandwidth game in the hopes of going IPTV. The idea was to finally ditch coaxial cables and to take advantage of better pricing.

I’ve always run my own router, relegating the ISP-provided equipment to a simple bridging configuration. However, I’ve been tied to Cisco (!) routers since beyond time, as we use Cisco equipment at work and I like the flexibility – and familiarity – that the equipment affords. The problem has been that Cisco equipment has tended to have lower overall throughput than the typical router you’d find on a shelf at Best Buy, while costing way more.

And the truth is that my Cisco config is somewhat more complex than a typical home router config. Sooo…. I stuck with my trusty 881 until I decided to pull the trigger on a 921-4P. The 921 gave me my full 150Mbps of downstream bandwidth – and then some – so I was in position to go the IPTV route.

That is, until SARS-CoV-2 hit and no self-install option was put forward for Digital TV customers to upgrade to IPTV.

Truthfully it may be a “blessing” in disguise, as I’ve read mixed reviews concerning the reliability of my provider’s IPTV offering. Most reviews are positive, but the last thing I need is for the WAF to drop due to inconsistent viewings of Island Life on HGTV.

But hey, at least my downloads became about 3x faster!

Switching gears. The next challenge was to revisit something that had been a thorn in my side for a long time. See, your typical Best Buy router may do something called NAT Hairpinning, which allows clients on the LAN to access local servers that have been given an address translation on the WAN side. Basically, you access a machine on the LAN using its translated public IP address. Cisco routers can do this as well using something called a NAT Virtual Interface – NAT NVI, or just NVI – but it saps performance. My 150Mbps (sometimes as high as 250Mbps+) dropped to under 100Mbps when running NAT NVI.

Why bother with NAT NVI in the first place? The truth is that I’ve been making do without it for a number of years now. I run my own internal DNS server which means that I can answer all DNS queries with the inside IP address. Why bother?

Google Nest Hub and Nest Hub Max, that’s why. We have a number of Google Assistant-enabled smart devices in our home, and for whatever reason Google has sought fit to have these devices try 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4 for DNS resolution before trying whatever DNS server you’ve assigned via DHCP. I’ve worked around this in the past by blocking access to Google’s public DNS servers, but Google got really crafty with the Nest Hub and Nest Hub Max and they started resorting to using DNS-over-TCP (encrypted DNS), and I think they even use the IPv6 addresses for their public DNS servers if IPv6 is enabled.

But wait – why is this a problem at all??? Who cares what DNS servers those devices use?

I care friend. I care.

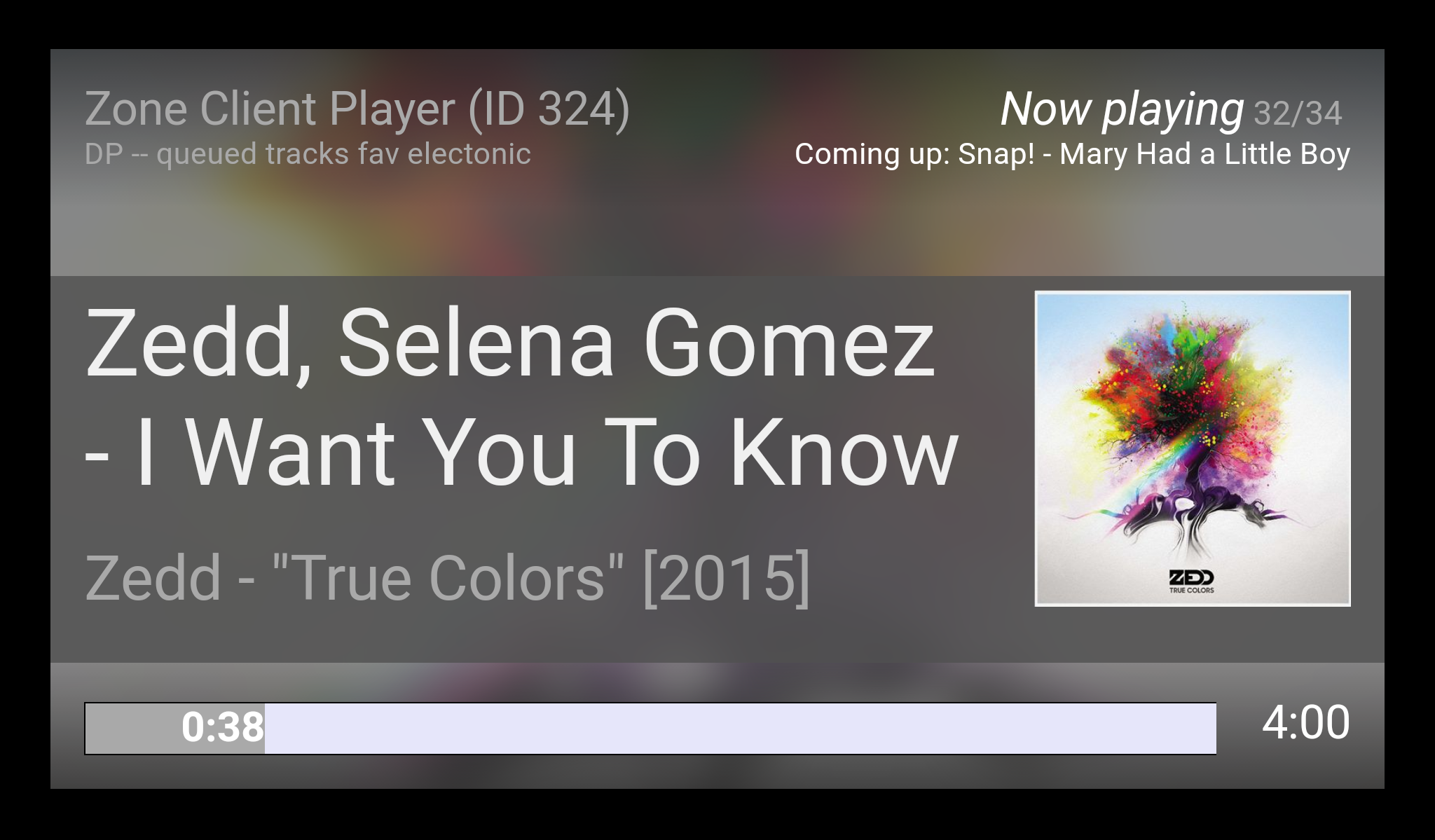

Actually, my Cast receiver app cares. The one I’ve written about ad naseum on this very blog. The one that’s hosted on my LAN and only really of use on my LAN. The one that allows me to throw my music around the house in whatever manner I see fit, rather than relying on Google Play Music, Google Flavour-Of-The-Month Music Streaming Service, or YouTube “Do you want to keep listening?” Music.

Running said Cast app requires that the Assistant and Cast devices connect to a server on my LAN. This requires that they resolve the URL registered with my app to an address on my LAN. This requires that they use the DNS servers on my LAN. If they don’t/can’t/won’t do this – like, oh, our Nest Hub friends don’t/can’t/won’t – then I can no longer cast my music to said devices.

So that was the dilemma.

And I’ll say again – this all worked with NAT NVI. But I wasn’t willing to take the throughput hit. It just didn’t seem right.

Also – congrats for making it this far.

You may be wondering: “How does IPv6 fit into all of this?” Well, IPv6 is something I had ZERO experience with prior to 2-3 weeks ago. But now? Hey, I’m running dual-stack my friend! IPv4 and IPv6 are in the house! I even rely on IPv6 as a solution to my Google Cast woes while still running traditional NAT and getting back my 150Mbps+ downstream goodness!

Here’s how it works:

I gave up (mostly) on trying to manage DNS for Google’s devices. If they want to use Google’s public DNS servers, they can use Google’s public DNS servers. In exchange, they have to resolve my receiver app’s URL using IPv6. In a nutshell: I changed the receiver app’s URL to one that only resolves to an AAAA (IPv6) record externally. Internally (on my LAN), that same URL resolves to an RFC1918 IPv4 address. If a dual-stack device attempts to resolve the URL using a public DNS server, it will get the IPv6 address. If it resolves using my internal DNS servers it will get the private IPv4 address.

The reason why this works is that IPv6 was designed so that NAT would not be required. The idea is that every device on the planet can have a unique, publicly-routable IPv6 address. Since NAT is no longer part of the equation for an IPv6 host, a Nest Hub Max that resolves my receiver URL to an IPv6 address will simply connect directly to the server’s IPv6 interface on my LAN. A device that resolves the IPv4 address will do the same, using the server’s IPv4 interface.

And any device that resolves the URL externally will hit the router (firewall) and go no further.

Seriously. That’s it. It’s crazy how simple it is.

Obviously the implementation is more complex than it seems. My public IPv4 and IPv6 allocations are dynamic. I’ve had a solution in place for some time to handle changes to my IPv4 public IP (nothing magical there, just look up Dynamic DNS for more info) but I had to figure out how to deal with changes to my IPv6 address. This also meant that I had to do some reading to understand how IPv6 works. As it turns out, my ISP gives me a /64 IPv6 prefix. This is combined with another unique 64-bit address to form the entire 128-bit IPv6 address for a particular host. The 64-bit host portion doesn’t change, so I only need to routinely check the IPv6 prefix and update my dynamic DNS entry when the prefix changes.

Things got even more complex because Apache needs to understand if a client is on the LAN or coming in from the WAN. This also necessitated upgrading my Apache server – which also became a good time to move it to another virtual machine. I won’t get into how I accomplished everything but suffice it to say that it was the most straightforward problem to solve in this entire mess.

So there you have it. Check back with me in a couple of weeks to see if everything is still working.